The engineer of the Amtrak that derailed in Philadelphia a year ago lost “situational awareness” after he diverted his attention to an emergency involving another train, the National Transportation Safety Board said this week.

Amtrak 188, a Washington-to-New York City train, was traveling at 106 mph — more than twice the authorized speed of 50 mph — when it derailed in a curve in Philadelphia on May 12, 2015. Eight passengers were killed and more than 180 others were sent to area hospitals, some with critical injuries.

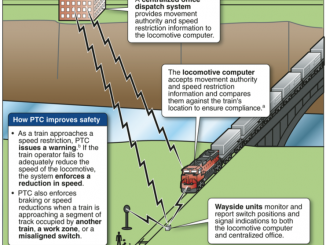

“It’s widely understood that every person, no matter how conscientious and skilled, is fallible, which is why technology was developed to backstop human vulnerabilities,” said NTSB Chairman Christopher A. Hart. “Had positive train control been in place on that stretch of track, this entirely preventable tragedy would not have happened.”

NTSB investigators who interviewed the Amtrak engineer described him as “very cooperative.” At the time of the accident he was not impaired by any substance and was not using his cell phone. There was no evidence that he was fatigued or suffering from any pre-existing medical condition while operating the train on the night of the accident.

In interviews the Amtrak engineer indicated that he was concerned for the well-being of a commuter train engineer, whose locomotive had just been struck by an object, spraying that engineer with glass from the windshield. The radio communications about that emergency, in which the Amtrak engineer participated and listened, lasted six minutes and, preceded the derailment by less than one minute.

Investigators determined the Amtrak engineer became distracted by the emergency involving the commuter train and lost situational awareness as to where his train was located in relation to the curve with the 50 mph speed restriction. The acceleration past 100 mph before entering the curve where the derailment occurred was consistent with a belief that his train had already passed the curve into an area of relatively straight track where the authorized speed was 110 mph.

The survival factors aspect of the investigation revealed some of the windows failed to remain intact throughout the accident sequence. Investigators said if the windows had not failed, some passengers who were ejected from the train and killed would likely have remained inside the train and survived.

In 1970 the NTSB recommended that then-available technology — that could prevent collisions, overspeed accidents and protect track workers — be implemented on the nation’s railroads; the NTSB has advocated for it ever since. At Tuesday’s meeting, NTSB members expressed frustration with the slow progress of positive train control implementation, which for passenger trains was previously required to be completed by the end of 2015 before Congress extended the deadline until 2018 and delayed enforcement of the regulation for two years beyond that.

“Unless positive train control is implemented soon, I’m very concerned that we’re going to be back in this room again, hearing investigators detail how technology that we have recommended for more than 45 years could have prevented yet another fatal rail accident,” Hart said.

The NTSB issued 11 safety recommendations in the report. The Federal Railroad Administration received five of the 11. Also receiving safety recommendations were Amtrak, the American Public Transportation Association, the Association of American Railroads, the Philadelphia Police Department, the Philadelphia Fire Department, the Philadelphia Office of Emergency Management, the Mayor of Philadelphia, the National Association of State EMS Officials, the National Volunteer Fire Council, the National Emergency Management Association, the National Association of Emergency Medical Service Physicians, the National Association of Chiefs of Police, and the International Association of Fire Chiefs. In addition to the 11 new recommendations made in this report, five other safety recommendations were previously issued during the course of the investigation.