While Positive Train Control (PTC) is perpetually a focus of railroads and lawmakers alike, the topic is hardly a new one.

Congress and federal authorities have expressed their interest in some level of automatic train control (ATC) for more than a century.

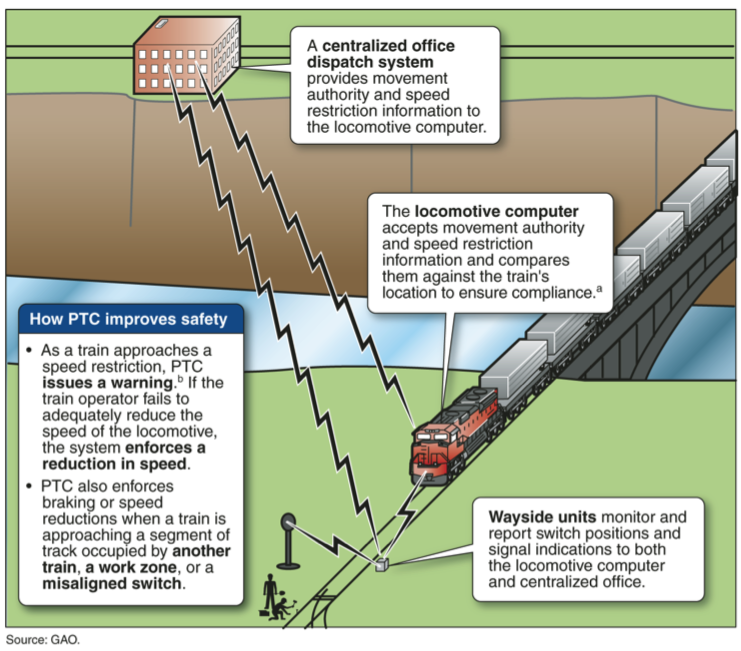

Congress mandated railroads implement PTC as part of the Rail Safety Improvement Act, which became law in October 2008. Railroads have installed PTC on 45,933 miles out of nearly 57,848 required route miles.

Early Attempts

Congress in 1906 directed the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), the predecessor to the Federal Railroad Administration, to investigate and report on the use of and need for devices for the automatic control of railway trains. Lawmakers also asked the agency to recommend such legislation as the agency deemed advisable.

“The need of additional safeguards to prevent accidents on railways must be admitted when we consider the enormous loss of life and injury to persons, and especially to the railway employes, which the railways of the country cause each year,” the Buffalo Illustrated Times quoted U.S. James Mann, R-Ill., a proponent of the legislation as saying in 1906.

“Railroading is nearly as hazardous in times of peace as being a soldier in time of war,” Man added. “Although Congress has provided for air brakes, automatic couplers and various other safety appliances, the installation of which has been proceeding during the last few years, yet, notwithstanding this, the percentage of railroad employes injured to those employed has been steadily Increasing.”

In the Transportation Act of 1920, Congress authorized the ICC to mandate the installation of ATS or ATC devices. The ICC in 1922 ordered the installation of these devices on 49 railroads on segments of track totaling about 5,000 miles.

Congress in 1937 enacted the Signal Inspection Act. This law required railroads to obtain ICC permission for any modification to their signal systems.

Post-War Efforts

Following World War II, in 1947, the ICC ordered any railroad operating at a speed of 80 mph or more (in essence passenger trains) to install ATS, ATC or cab signal systems.

In a report that same year, the ICC noted that ATS or ATC was in use on more than 14,100 miles of track, while cab signals were in use on more than 8,100 miles. The ICC estimated its order would require such devices on an additional 27,156 miles of rail line.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued its first recommendation regarding automatic train control to the FRA in 1970. The suggestion came after its investigation of a 1969 crash involving a commuter train and a work crew train in Darien, Conn.

It recommended the FRA “study the feasibility of requiring a form of automatic train control at points where passenger trains are required to meet other trains.” In 1976, the congressional Office of Technology Assessment issued a report requested by Congress on the use of automatic train control devices in rail transit systems.

In 1983, the FRA proposed changes to signal and train control requirements. In issuing its final rule, citing the 1947 ICC threshold of 80 mph for installation of ATS, ATC, or cab signal devices, the agency determined there was no compelling argument to either lower or raise the 80 mph speed threshold.

In 1990, the NTSB placed automatic train control on its initial “Most Wanted List of Transportation Safety Improvements.”

The Last Quarter Century

Congress directed the FRA to issue a progress report on positive train control in The High-Speed Rail Development Act of 1994. In 1997, after an investigation of a crash between a commuter train and an Amtrak train in Silver Spring, Md., that killed eight commuter passengers, the NTSB recommended that the FRA require the installation of a positive train separation control system for all tracks where commuter and intercity passenger railroads operate.

The FRA responded in 1998 to the NTSB’s recommendation by stating, in part, the “answer to this problem is more affordable technology and commitments for joint action by freight and passenger service providers. It is important that we avoid any burden on passenger service providers that would result in service cutbacks and diversion of passengers to less safe forms of transportation.”

In 2004, the FRA submitted a cost-benefit analysis of PTC at the request of Congress. That study showed that as of 2004, the costs of PTC outweighed the direct safety benefits, but the agency’s letter to Congress stated, “we believe PTC will be more affordable in the future.”

This article was, in part, adapted from a Congressional Research Service report.