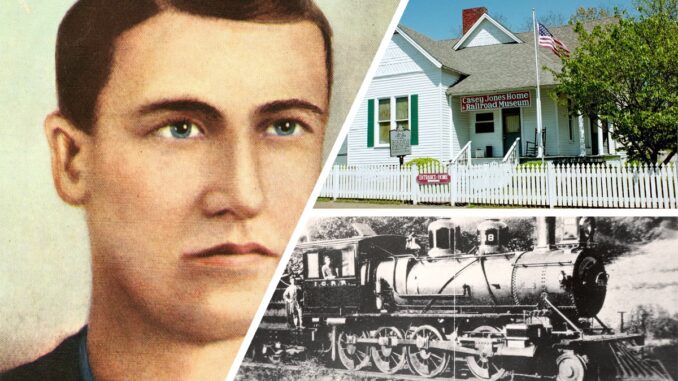

In the early morning of April 30, 1900, John Luther “Casey” Jones, filling in for a sick engineer, sat behind the throttle of engine No. 382, pulling the Cannonball Express.

The Cannonball pulled out of the Memphis train station at 12:50 a.m., about 90 minutes behind schedule. By the time Jones reached Durant, Mississippi, he had made up almost all of the train’s lost time.

“Telegraph poles whizzed past like the pickets of a fence,” Fred J. Lee wrote in his 1940 biography of Jones.

“But to Casey Jones, every cattle guard, every mile post, every dim landmark was as the page of an open book,” Lee wrote. “His hands left the throttle and airbrake lever only when it was necessary to bear down on the whistle chord. Folks along the right of way, snug in their beds and only drowsily conscious, shot broad awake when No. 382’s whistle sent the mournful chime of the whippoorwill call echoing across the countryside.”

At Vaughan, Mississippi, two freight trains – a northbound and a southbound – shared a siding but were too long and blocked the main line. Historians estimate Jones was traveling about 75 m.p.h. when he hit a warning torpedo on the train tracks and tried to stop the train.

Realizing he would be unable to avoid a collision, he told his fireman, Sim Webb, to jump from the train and save his life. The move secured Jones’ place in not only railroad history but American folklore.

Jones, who lived in Jackson at the time of his death, is immortalized in song and folklore.