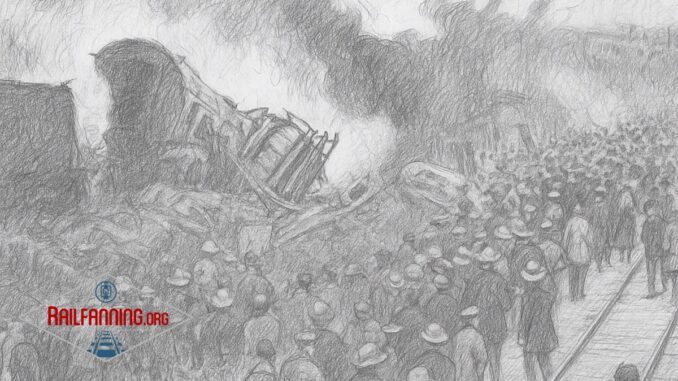

On a warm June night in 1918, the sleepy community of Ivanhoe, Indiana, was the backdrop of one of the deadliest railroad disasters in the county’s history: The Hammond circus train wreck.

What began as a routine westbound journey for the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus ended in horror just east of Hammond, Indiana. Some estimates indicate that at least 86 people were killed and another 127 injured in the June 22, 1918, wreck.

The first train, Extra 7826, had seven stock cars, 14 flat cars laden with circus wagons, a wooden sleeping car, and a caboose. It departed Michigan City shortly after 2 a.m., carrying 400 performers and roustabouts with the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus and equipment bound for a summer engagement.

A flagman alerted Conductor U.W. Johnson of a blazing hot box on one of the flat cars, and the train stopped near Ivanhoe’s Elgin, Joliet & Eastern crossing. While crews inspected and managed the hot box, the train resumed its slow advance under caution signals.

Behind them, a Michigan Central Railroad 21-car sleeper extra train left Michigan City at 2:57 a.m., operating under a clear signal for its entire run. Alonzo Sargent was at the throttle of locomotive No. 8485, a Michigan Central/New York Central class K80r 4-6-2 Pacific, traveling from Detroit to Chicago.

The train passed a caution indication, then a stop signal at the interlocking plant just east of the crossing. Believing the track ahead clear, he continued forward and into the rear cars of the circus train at 3:57 a.m.

The Michigan Central train crashed into the circus train’s caboose and four rear wooden sleeping cars. The impact sheared cars from their trucks and ignited the wooden sleepers.

The wreckage burned with a heat so intense that rescuers had to wait hours before approaching the remnants.

By dawn, rescuers counted 67 circus performers and patrons dead, along with one Michigan Central employee. Another 127 people were injured, many with burns and fractures suffered as cars collapsed and burst into flames.

Sargent had fallen asleep at the throttle of No. 8485, missing the home signal’s red indication and the frantic warnings of the circus train’s flagman, who struggled back along the rails to protect the stalled train.

Sargent had had little sleep in the preceding 24 hours. The lack of sleep, coupled with Sargent eating several heavy meals, taking kidney pills, and the gentle rolling of his locomotive, likely caused him to fall asleep at the throttle.

Wooden-framed sleeping cars, the reliance on oil lanterns for lighting, and the absence of fail-safe signaling systems all contributed to the high toll. In the following years, railroads increasingly adopted steel-bodied cars, automatic train control devices, and stricter operating rules to keep engineers alert and track segments protected.

Sargent and his fireman, Gustave Klauss, were criminally charged in Lake County, Indiana.

An investigation by the Bureau of Safety — later integrated into the Interstate Commerce Commission — blamed human error for the tragedy.

Following a trial, a jury deadlocked, and a mistrial was declared. Prosecutors declined to retry the case, and charges were dismissed on June 9, 1920.